Peter Meyer continues his conversation with Maria Coler about all things Brownfields in a second installment.

By Steve Dwyer

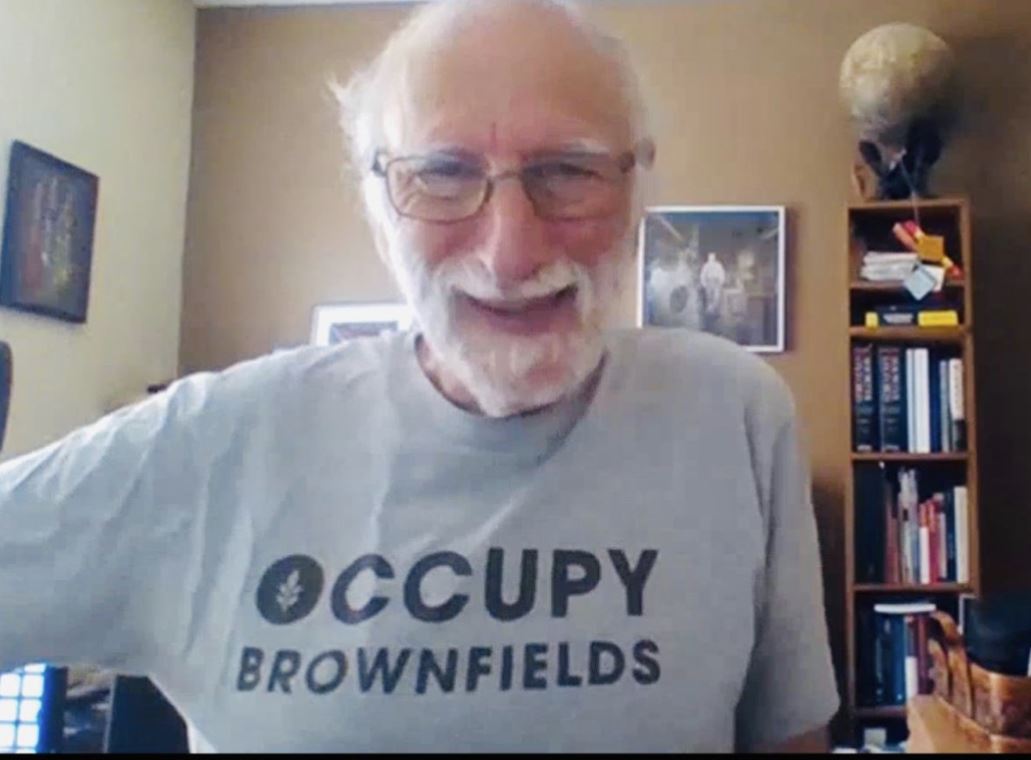

Everyone remembers the “Occupy Wall Street” movement of a decade ago. Peter Meyer certainly does. And he has a story and T-shirt to give it some interesting context.

Meyer, Professor Emeritus at University of Louisville (UL) and president of The E.P. Systems Group Inc., recently spoke via a Zoom call with Maria Coler about a host of brownfield-related themes, including memories of his friend Charlie Bartsch, who passed in 2017.

One of the aside questions Coler posed to Meyer was the motivation behind his “Occupy Brownfields” T-shirt, which he was wearing during their conference call. So what’s the significance of the shirt?

The T-shirt was inspired by the “Occupy Wall Street” movement that began in Zuccotti Park in New York City’s Wall Street financial district in September 2011—giving rise to the wider Occupy movement for social and economic changes in the United States and other countries.

“I attended a brownfield conference with Charlie years ago … it would have been when “Occupy Wall Street” was occurring,” says Meyer, who served as director of the Dept. of Urban and Public Affairs at UL. With a PhD in economics, Meyer had been director for the Center for Environmental Policy and Management at the university from 1988 to 2008. “Charlie ran up to me saying that they were handing out these T-shirts, so I guess I owe this T-shirt directly to the influence of one Charles Bartsch.” (Editor’s Note: Dan French of Brownfield Listings conceived of the slogan and sold the T-shirts at the aforementioned conference.).

When you think about it, Meyer mused, the thread that connects the two “movements” are the economic and social aspects that serve as underpinnings -- but in far different contexts. To “occupy brownfields” can be taken literally -- such as, “someone please develop and execute a new and compelling end-use for this pre-existing parcel in some urban infill.”

Meyer explained further, without wanting to get too political: “The significance of the Occupy Brownfield concept is that we don’t want to abandon any of our assets, one of which happens to be brownfields, and I can leave it at that.”

Read ahead to get inside the extended conversation between Meyer and Coler, President of HCI Hydrotechnology Consultants Inc., located in Jersey City, N.J., and chair of the BCONE Scholarship Committee.

MC: The intersection of your background with brownfields seems to be in the environmental justice (EJ) and social justice arenas, where you have these depressed area which were once highly productive, industrial centers. The export of jobs overseas resulted in towns/regions no longer being economically viable. The brownfields industry tries to answer this question: What do we do with the hulking masses of our industrial past that have been leftlying fallow?

PM: That is accurate -- my motivation is what you just said. Charlie and I were extremely concerned with the issue of "economic regeneration," if you will, of these abandoned areas. And that's what motivated him at The Northeast-Midwest Institute, where that was the biggest priority. Certainly, it was a major one of mine. I think that was the essence of it. And that was sort of where the pieces came together ... to focus specifically on contamination. Surely he was unquestionably one of the very first, if not the first, professionals who had an innate concern about brownfields and supported the whole EJ initiatives at the EPA.

MC: Can a constituency around the intersection of environmental, economic and social issues be formed? Looking at Charlie, you had indicated he had the personality and expertise to bring people to the table. So, in looking at the lack of integration to form a constituency around the Biden administration's physical and social infrastructure pieces of legislation, Charlie seemed to have a deep understanding of all the different parts and could inform that desire to integrate these pieces better. Can you elaborate further?

PM: Assuming that he was given access, let’s start with the basic question. With regard to recent legislation, I think that the way it came together is that there was an advocate for this piece that was not good for that piece. There was an advocate for the advocates. Each of those pieces needs … to get sufficient political lift, to be part of it.

Charlie would be acutely aware of the fact that there were no such constituents. Because that was one of the things he kept talking to me about with regard to this manufacturing initiative: "Who the heck is going to back this thing if we ever write it?" That’s true. And he was very concerned with that. But that didn't mean that he could, or anybody could, successfully get them adequately integrated.

It’s part of the reason that we have all of these unintended consequences of legislation. You know, long before I got into brownfields with Charlie I ran across the younger brother of a friend of mine who was working in the water department in the City of New York. And CERCLA had just passed when he turned and said to me, "Peter, you’re an economist. Look into this. I have no idea. You really need to look into this. Will the just-passed legislation disadvantage cities in terms of getting investment in a large-scale economic development versus any development outside?"

MC: I wrote a long email to Senator Cory Booker’s staff about brownfields -- how to use big data and how to integrate [all of the moving pieces]. I said, "I have the answer for you, a path forward." The takeaway is how to get beyond this old language, this old way of thinking about it, this "silo-ing" of information, how you bring these pieces together to effect real and lasting change. It hasn’t worked yet. And there’s a reason it hasn’t worked: I think in this conversation we have stumbled upon that reason of why it hasn’t worked. And the reason is that it’s lacking this magic—a sustained, integrated, enthusiastic passion.

PM: I think that you’re completely correct.

MC: I think the key is to almost channel Charlie’s spirit and to ask, "What would he think about this question? Would this question excite him?" With this question in mind, would he sit down with a beer or a glass of wine and talk about it -- for a few hours? What do you think?

PM: I think I can answer that. I think about the issue of climate change, brownfields and land reuse and redevelopment. The incredible migrations that are likely to happen as a result of climate change: These were all topics of concern that I was already talking about with Charlie. There’s no question that we were already kicking some of that stuff around.

MC: I mean, this very specific problem of "rebranding" this whole effort -- it’s really a rebranding exercise.

PM: If Charlie had participated in the conversation we’ve had for the last hour and a half, he’d be sitting there right now interested, engaged -- 100%. He desperately needed and wanted to sell the brownfield investment. There were periods in which there were brownfields conferences, going back where Charlie spoke eight to 10 times ... because he was so good. You go back to the earlier brownfield conferences, look at an agenda and type in the word, "Bartsch" and you'll find incredible numbers. He was able to speak on whatever it was over and over and over again. He thought he failed when he only had three slots at a conference.

Now he’d be very, very happy. He’d be going places where other people would be afraid to go. Or, he’d even see some ways of moving forward that the rest of us wouldn’t even notice were there. I miss him personally, but boy do I miss him from a policy standpoint. We need him so badly or the equivalent of him right now in this country. Like nothing I can imagine. It’s a rare, rare human being -- that’s all I can say. Boy do we need somebody like that.

Posted January 3, 2022