By Steve Dwyer

Here are more compelling textbook examples of young, would-be brownfield professionals stepping up with fresh sets of eyes to help see a productive way forward in the redevelopment of brownfield properties in 2022 and beyond.

We’ve reported on many university and college efforts tied to scholarships as the stake. The most recent was a team from Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, N.J., who were scholarship recipients following their participation in “Perspectives in Environmental Management,” a course taught by Dibyendu “Dibs” Sarkar, Professor, Civil, Environmental and Ocean Engineering, at Stevens Institute of Technology.

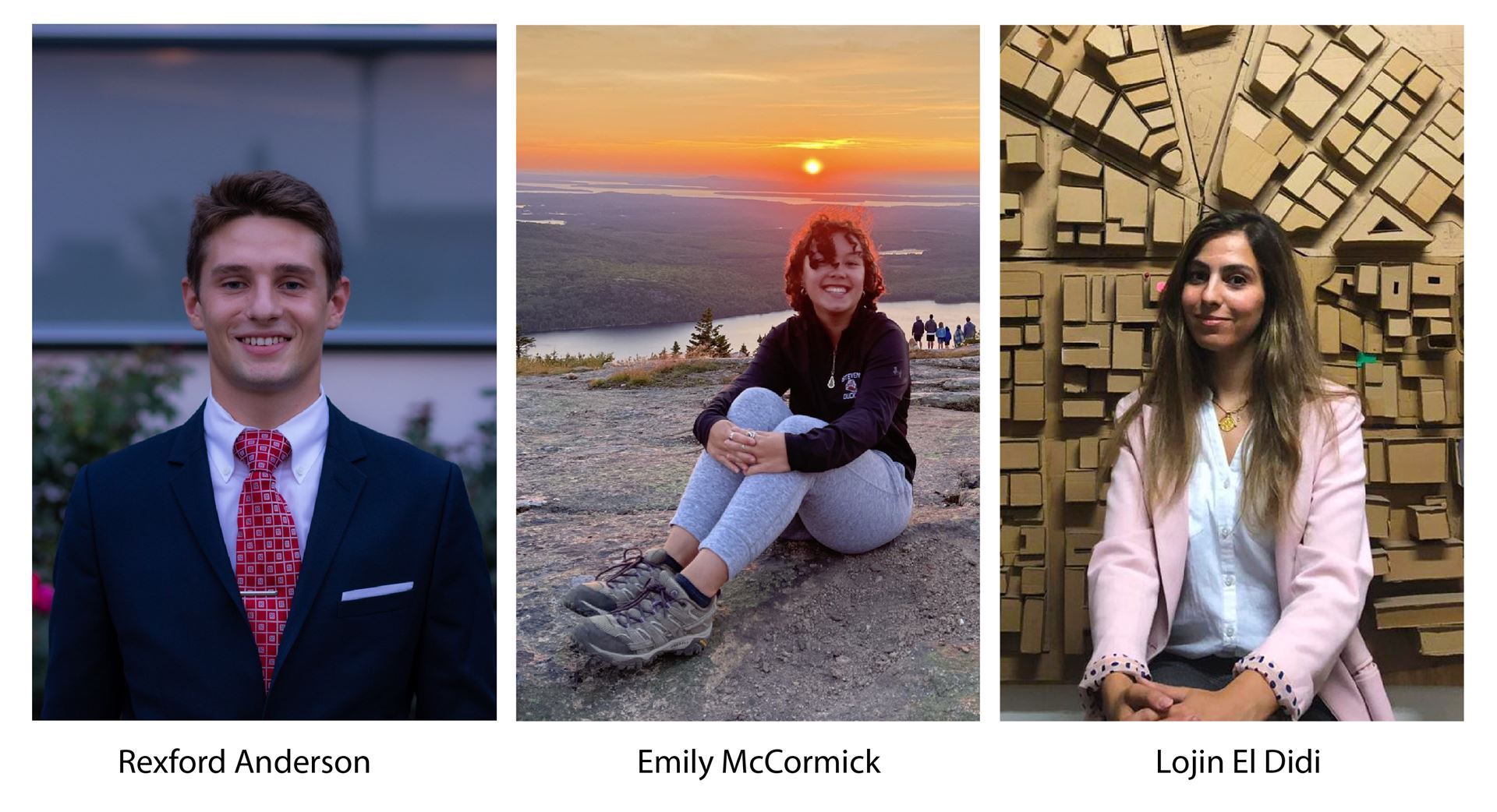

The teams competed for the Brownfield Coalition of the Northeast’s Charlie Bartsch Scholarship Fund cash award of $2,000. The winning team members include the following students:

- Rexford Anderson, graduate student, Business and Sustainability (dual degree)

- Emily McCormick, undergraduate, Biomedical Engineering

- Lojin El Didi, graduate student, Sustainabilty.

Recently, Maria Coler, president of Hydrotechnology Consultants, Inc. (HCI) and a chair of the BCONE Education and Scholarship Committee, spoke to Dr. Sarkar along with three scholarship awardees during a virtual post-award interview. Coler began by asking Dr. Sarkar to describe what the class assignment was and to provide some background on the “Perspectives in Environmental Management” class.

Describing the most recent class experience, Dr. Sarkar said: “This was a great group because they had a lot of synergy, and one objective of the assignment was to give them the opportunity to learn] how to work in teams. I think they did that beautifully. There were two graduate students and one undergraduate in the winning scholarship group.

He continued: “They had a lot of independence, and teamwork was evident,” with a goal to develop a green and sustainable urban environmental justice plan for communities.

Dr. Sarkar, whose research focuses on understanding the behavior of inorganic and organic contaminants in the environment, says that the goal of the four teams (a total of 24 students) was to hatch an economically feasible plan of development in the city or town of their choice.

Dr. Sarkar—who works to examine how contaminants behave in various environmental media, such as soil, water, sediments and biota to determines their ultimate fate—says that one overarching goal is to “prescribe appropriate remedial measures to lessen ecological and human health risks.”

He cited various vulnerable areas in New Jersey, including Newark, that are prone to flooding and rife with water quality issues—a chronic problem that “typically goes hand in hand” in densely developed areas of New York and New Jersey where sewage accumulates whenever it floods. “The whole idea was for them to look at various green forms of ]infrastructure,” says Dr. Sarkar, a strong believer in an interdisciplinary approach to solving environmental problems.

‘Amazing Effort’

During the virtual session, Coler was impressed about the team’s visionary and cohesive effort to wring results.

She added that the next steps with projects such as these is determining how to “bring life back to the soil and groundwater”—rather than “just removing the contamination—how can we make sure this can become a living ecosystem again so there’s ongoing ecological]value.”

One aspect Coler underscored was that when it comes to complicated brownfield efforts—which ones are not?—various stakeholders might be inclined to run from the problem, apprehensive to move forward. However, “not being afraid of these sites, but embracing them for their historical and cultural and environmental value” is what sets the successful stakeholders apart from the others.

As a professional and president of HCI, Coler has been able to see multiple productive ways forward to ensure successful redevelopment efforts across the Tri-state region. She emphasized that the endgame is “connecting brownfields to the greater arc of the sustainability movement and also to environmental consciousness in general.”

Speaking to the Stevens students, Coler said that “it’s a great time to do what you’re doing, that you're making that connection--the micro and the macro world, the human world and the natural world. Seeing that continuum is so important. But, we are in trouble to garner results and success because people operate in silos….We can all see the bigger picture together and use our skill sets to solve the problem.”

Dr. Sarkar made clear that the winning team stepped up to the challenge. “Overall, the package was really impressive, in my opinion. They took their jobs seriously and did a lot of homework,” citing such functionality as deploying cloud data to assess community flooding impacts,

“When they presented, it clearly showed they were not presenting for the first time: they already practiced it and did a very good job in making the presentation,” he says. “I was extremely satisfied with the work of the team. Every year, new teams come and they lead, but I will remember most of the work by this team—and perhaps I will use their effort as a model for next year.”

Dr. Sarkar, whose received his Honors B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in geology from the University of Calcutta, India, an his PhD in Geochemistry from the University of Tennessee, made mention of how the team was ultra-diversified, which was not always the case in past years. The team members are pursuing careers across architecture, business and engineering fields. Dr. Sarkar called it a case of “cross-disciplinary excellence.”

Added Coler about the elusive goal of being profitable and at the same time engendering green practices and sustainability, “It’s encouraging that the Stevens team sees that. Having a profitable business is not mutually exclusive to having a sustainable business. It's not hard to have a profitable company in this world…if you don’t care about the environmental and the social good. The real geniuses are going to be the ones that actually pull off being financially solvent and sustainable.”

Team Members Chime In

Rexford Anderson, Emily McCormick, and Lojin El Didi spoke during the Zoom session about Stevens Institute and how they came into Dr. Sarkar’s course, how it spawned the effort that led to their scholarship.

Anderson finished his undergraduate work at Syracuse University, where “I studied finance and supply chain management.” Speaking of his penchant to appreciate sustainability, “I’d always enjoyed being outside and being in nature. I was a Boy Scout growing up and went all the way through to Eagle Scouts, so the environment was always a priority.”

Captivated by a green supply chain course at Syracuse, Anderson was able to see and appreciate “the connections between the business world and sustainability,” and how sustainability can be baked into the overall process. “I wanted to continue my education in sustainability and came to Stevens seeking a dual business and sustainability degree. I was hooked from there. I absolutely love the program so far.”

He spoke about other topics during the one-hour call, including:

Use of technology: “When we first started we kind of looked at flood maps to see where the highest flood areas were—flood searches during hurricanes to determine where all of the water accumulated and then, from there, we narrowed down a couple of cities that we might want to target.”

Financial analysis: “Once we had narrowed down those cities, we performed the financial analysis to see if it fell into the category of environmental justice or not. We further narrowed it down and ended up in Newark, there were a couple different streets, and leaned a little more towards South St. The advice we were given was to look for a street that has a slope to it. We also looked at Google Earth to…see what the actual slope was and how that changes over time. You can get a good idea of where the water will pool, and can then proceed from there.

What was learned: “What we first thought of when looking at the brownfields website, examining water contamination. By identifying the brownfields, we looked at solutions to divert water away to minimize any kind of contamination. Afterwards, we designed it around that to cultivate the water towards the center and towards the corners.”

What we learned about the brownfields in Newark is that there are a lot of them. And it is a very large issue to remediate them, and putting land back into an actionable use.

Emily McCormick, unlike her other two teammates, participated as an undergrad student, studying for a degree in biomedical engineering. “Growing up, I was always advocating for public health aspects in terms of what I wanted to do for my profession—both my parents are pharmacists.

What she always sought: “I knew I wanted to do something with biomedical engineering, but I've always been really into the outdoors. My parents raised me to know and respect other animals and plants. It’s something that I always talk about with my friends and try to be sustainable, and I wanted to take it to a professional route. I minor in green engineering and the perspectives and environments management was my first course. I learned a lot and I hope to take that further with my public health degree with biomedical engineering.”

Ideas about green infrastructure: “I think most of the groups had similar ideas of what kind of green infrastructure we were supposed to implement—accessible to the public and better for the community. We ended up being a lot more specific in terms of what we wanted to implement. We had to establish that there was a slope on Newark’s South Street, and we knew where the brownfields were. My engineering background allowed me to know the different types of dimensions that we would have to implement and how wide the street was to create permeable pavement.”

Lojin El Didi, experienced an acute awakening about how she perceived brownfield sites during Dr. Sarkar's course. She learned about brownfields via the class and is now interested in the historic preservation and architectural aspects of brownfield redevelopment.

It's a refreshing epiphany by the student, who stated that “before I started this course, I never thought about brownfield redevelopment much,” at least in the context of how architecture fits into the overall tapestry.

When you think about historic preservation, Lojin likened brownfields to ancient site preservation in Egypt. When she was in Cairo, she witnessed residents “literally being kicked out of their homes. I thought that was very unfair. I had a lot of friends who were in architecture and they were trying to fight it. This became a passion to me because I did see how those people got affected.”

Lojin, with a background in architecture in urban areas, is eager to advance her career to advocate for architecture strategies that tie into the brownfield development mission—and not only to espouse historical legacies and sustainability, but to see to it that people don’t have to flee their homes. One solution to that is to champion for middle- to low-income affordable housing on brownfield sites.

“When I started this course I began to better connect architecture to sustainability.” When it comes to legacy buildings in the urban infill, residents have a profound memory about their industrial past, and it’s often a priority to maintain these buildings. “It’s like an open book: you can see it, you can touch it, and it interacts with you as well. It gives you a sense of what it looked like in the past.”

She adds: “A garden can make a change in the community: It’s very small but can make a huge difference in the community. I’m very passionate about sustainability—developing urban areas. That’s what drove me to this course.”

Posted June 16, 2022